EDITOR’S NOTE: February is Black History Month

By Diana Chandler

Baptist Press

Kelly Miller Smith, Jr., preaching Sunday (Feb. 16) during a yearlong bicentennial celebration at Nashville First Baptist Church, exhorted Christians to love with the compassion characteristic of Jesus. — Photo by Scott Schrecker

NASHVILLE — Nashville First Baptist Church was willed an enslaved 16-year-old Nelson G. Merry in 1840, and by 1853 had baptized, discipled, freed and ordained him to pastor the First Colored Baptist Mission, a First Baptist church plant.

That church plant became First Baptist Church Capitol Hill, a majority black Nashville congregation led by senior pastor Kelly Miller Smith Jr. He participated Sunday (Feb. 16) in Nashville First Baptist’s yearlong bicentennial celebration, preaching the morning sermon and answering questions on race relations and civil rights during a luncheon afterward.

“Our congregation was born at a time when slaves were just being freed after the Emancipation Proclamation,” Smith told Baptist Press. “From the time of inception, Nashville First Baptist seemed to understand the value and importance [of] former slaves having their own identity and approach to worshiping and serving God. It is evident in our shared history.”

Smith and Frank Lewis, pastor of the mother congregation Nashville First Baptist, are longtime friends, having met more than 20 years ago when both served on the Board of Trustees of Belmont University. Lewis, who has collaborated with Smith in several racial reconciliation initiatives, told Baptist Press the slavery is what he most regrets about the history of Nashville First Baptist.

“Every encounter I have had with the membership and leadership of First Baptist Capitol Hill has been an expression of grace and forgiveness, that seems to be based on a shared hope for a better future,” Lewis told BP.

Nashville First Baptist traces its beginnings to an 1820 Nashville revival led by Jeremiah Vardeman and James Whitsitt. Sunday marked the second guest sermon in a series of speakers and monthly mission emphases scheduled as First Baptist Nashville prepares to officially mark its bicentennial July 19. The day included two special Sunday School classes focusing on racial reconciliation and taught by teachers from First Baptist Capitol Hill, Smith’s 10:30 a.m. sermon and a luncheon Question and Answer with Smith and Nashville School Board member Sharon Gentry, a First Baptist Capitol Hill member who led a Sunday School class. Also teaching was Susan Howard.

Smith, 64, grew up in Nashville during the civil rights struggle of the 1960s, when his father Kelly Miller Smith Sr. pastored First Baptist Capitol Hill. Smith’s father was a leader during the struggle. Smith said Sunday his father often had to evacuate his family from their home in the middle of the night after receiving bomb threats, never certain whether an explosion was imminent.

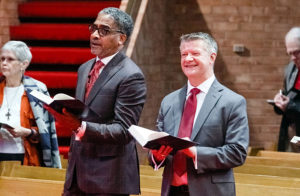

Nashville First Baptist Church Senior Pastor Frank Lewis, right, sings during Sunday (Feb. 16) morning worship with First Baptist Church Capitol Hill Senior Pastor Kelly Miller Smith, Jr., during a yearlong celebration marking Nashville First’s bicentennial. — Photo by Scott Schrecker

The struggles of the age still trouble Smith, who believes Christians fall short in demonstrating the compassion of Jesus.

“There were times when my sisters would walk to school and some of the boys would sic dogs on them. There were times when [segregationists] would call and threaten my dad, because of him trying to do the things he felt were right,” Smith said. “This morning as I was preaching and as I was reflecting upon how to approach the message for today, I am greatly concerned about particularly the lack of compassion that is prevalent not only in Nashville … but on the national front as well.”

While evangelism is crucial, Smith said, he is more concerned about Christians not taking on the characteristics of Jesus Christ.

“We do not suffer with others,” Smith said, alluding to the sermon he’d preached an hour earlier from Mark 1:40-42, when Jesus healed a leper. “That’s one of the things that got Jesus into trouble, is … He spent too much time and energy identifying with persons who were not persons of power, not persons of class and responsibility. He was not in those safe environments when he would deal with those persons who had leprosy, deal with those persons who had all kinds of illnesses, and demon-possessed persons who were ostracized.

“He was dealing with women; he was dealing with children; he was dealing with persons who had other kinds of things that society was not willing to embrace. We as a church have to get to that,” Smith said. The church must “get to that core of trying to demonstrate the issue of compassion.”

During the luncheon, Smith urged listeners: “Instead of seeing yourself — as the majority of the persons here – as white, see yourself as an African American.”

For Lewis, slavery is the most troubling thing about Nashville First Baptist’s 200 years.

“How anyone could have ever justified slavery, or could have possibly found biblical support for the dehumanizing behavior that lies in our history is unfathomable,” Lewis told BP. “We are created as image bearers of God. The dignity of being and recognizing the image of God in all of humanity requires that we repent of our actions from the past.

Kelly Miller Smith Jr., pastor of First Baptist Church Capitol Hill in Nashville, with his mother Alice Smith Risby attended the December 2019 unveiling of a historical marker recognizing Nelson Merry, a formerly enslaved man Nashville First Baptist Church ordained as the first black pastor in Nashville in 1853 to lead what was then the First Baptist Colored Mission. — Photo submitted by Kelly Smith

“This includes the practice of slavery, the inhumane history that led to the civil rights movement, and current injustices that reflect prejudice and racial bias today,” he said. “As an individual I have done this. As a church, we have done this and attempt to model a commitment to loving our neighbor as ourselves today.”

First Baptist Capitol Hill traces its birth to a May 26, 1866, charter obtained after the colored mission petitioned Nashville First Baptist for independence, granted Aug. 13, 1865. Merry had begun pastoring the mission in 1853. When Nashville First Baptist ordained him, he became the first black ordained pastor in the city, and led until his death in 1884 what was then First Colored Baptist Church. The Historical Commission of Nashville and Davidson County erected a marker in December 2019 recognizing Merry as the first ordained black pastor in the city.

The church had grown from 780 to 2,800 members under Merry’s leadership. Today, the Capitol Hill congregation cooperates with the National Baptist Convention USA, Inc.

History records Merry as founder of the Tennessee Colored Baptist Association in 1866. He edited The Colored Sunday School Standard and frequently attended regional and national Baptist church conferences.

“When you read about the way Nelson Merry was discipled by men in our church during that time, it says to me that someone back then took a risk because they had a hope for a better future for mankind. I am proud of that,” Lewis told BP. “Read Nelson Merry’s story and you discover that he became a significant leader, church planter, pastor, and minister at large. It is a great example of how the Gospel is a redeeming story.

The current Nashville First Baptist Church building retains the tower from an earlier building constructed in 1886. The congregation in downtown Nashville is marking its bicentennial with a yearlong series of guest preachers and mission emphases. — Photo by Scott Schrecker

“A woman dies and gives her estate to the church. That estate included a slave. The slave was given his freedom and employed by the church. He was mentored before mentoring was cool,” Lewis said. “Then he becomes the pastor to the members of the church who had been slaves. Somehow, he instilled into the DNA of the churches he started, the grace of forgiveness. It is a story about the triumph of the Gospel, but it is a story that we still have to be intentional about every single day.”

Both Lewis and Smith value their friendship and plan to continue leading their congregations in love for all mankind.

“Dr. Lewis and I have shared lunch, life stories, worship and ministry together. He has a gracious spirit that is willing to even break some traditional perspectives,” Smith told BP, referencing a 2018 Nashville Christmas parade Nativity scene when the churches collaborated on an integrated couple as Mary and Joseph, with an African American Jesus.

Friendships are vital, Lewis told BP, “if Christians are going to continue the journey of racial reconciliation; but I find it hard to believe that they would be possible without the Gospel. I think that is what I appreciate most.

“You see the effects of the Gospel at work when we share a meal, bump into each other at Kroger, walk side by side in a memorial march or a Christmas parade, sit with each other in worship, and plan events that are intentionally focused on the unity that is ours in Christ.” B&R