By Aaron Earls

LifeWay Christian Resources

NASHVILLE — When a pastor commits adultery, most of their fellow pastors believe they should withdraw from public ministry for at least some time.

NASHVILLE — When a pastor commits adultery, most of their fellow pastors believe they should withdraw from public ministry for at least some time.

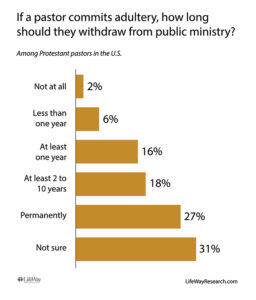

A new survey of U.S. Protestant pastors by Nashville-based LifeWay Research finds 2 percent of pastors believe a fellow pastor who has an affair does not need to take any time away.

“Scripture doesn’t mince words about adultery,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of LifeWay Research. “From the Ten Commandments, to the Apostle Paul’s lists of wicked things, to the qualifications for elders listed in 1 Timothy, adultery is not appropriate for a follower of Christ nor a leader of a local church.”

Few believe less than a year is a sufficient period of withdrawal from public ministry: 3 percent say for at least three months, and another 3 percent say at least six months.

Around 1 in 6 pastors (16 percent) believe an offending pastor should stay gone for at least a year.

Other pastors want them to be away from public ministry for a longer period of time: 10 percent say at least two years, 7 percent say at least five years, and 1 percent say at least 10 years.

For more than a quarter of pastors (27 percent), a pastor who commits adultery should withdraw from public ministry permanently.

Three in 10 pastors (31 percent) say they aren’t sure what the appropriate time frame would be.

“While the Bible is clear that this behavior does not fit a pastor or elder of a church,” said McConnell, “there is much debate over how long this act would disqualify someone from pastoral ministry.”

Changes since 2016

Pastors’ responses are similar to though not unchanged from a 2016 LifeWay Research survey.

Pastors today are less likely than those four years ago to say shorter time frames are appropriate periods of withdrawal from public ministry.

Compared to 2016, pastors now are less likely to say less than a year (6 percent to 10 percent) or at least a year (16 percent to 21 percent) is the right amount of time away.

“There has been much attention given to calling American leaders to account for sexual misconduct since 2016,” said McConnell. “It is not surprising that fewer pastors believe public ministry should be restored in a year.”

Overall, there is more uncertainty among pastors now. Current pastors are more likely to say they are not sure of the appropriate time away from public ministry today (31 percent) than in 2016 (25 percent).

Differences among pastors

The ethnicity, education and denomination of a pastor influenced the likelihood of their response.

African American pastors are the least likely to say one who commits adultery should withdraw from the ministry permanently (8 percent).

Denominationally, Pentecostal pastors are the least likely to advocate for a permanent withdrawal (6 percent) and most likely to support staying away for at least a year (35 percent).

Methodists (7 percent) are more likely to say the pastor does not need to withdraw at all than Baptists (1 percent), Lutherans (1 percent), Pentecostals (less than 1 percent), and pastors in the Restorationist movement (less than 1 percent).

Pastors with a bachelor’s degree (34 percent) are more likely to support a permanent withdrawal than those with additional education: master’s (27 percent) or doctoral degree (22 percent).

Smaller church pastors, those with churches of attendance between 50 to 99, are also more likely to say pastors who commit adultery should withdraw from ministry permanently than pastors of churches with 100 to 249 in attendance (31 percent to 23 percent).

“Pastors’ opinions on the subject are a good barometer for opinions across churches,” said McConnell. “There is widespread disagreement from pastors across denominations, church size, age, race and education levels to quickly restoring pastors who commit adultery to public ministry positions.” B&R