BP EDITOR’S NOTE: Sanctity of Human Life Sunday is Jan. 19 in the Southern Baptist Convention.

By Tobin Perry

Baptist Press

Shaq Hardy preaches during a youth gathering at Brainerd Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tenn. Abandoned by his mother not long after birth, Hardy often leans on his experience in foster care to minister to hurting kids. — Photo courtesy of Shaq Hardy

CHATTANOOGA — Much of Shaq Hardy’s childhood is a blur. For the first 10 years of his life, he moved from foster home to foster home, never able to put down roots.

Hardy longed for a sense of home, a place where he belonged.

But what Hardy does remember during that frantic decade in foster care is where he learned John 3:16 and how much Jesus loved him. Although he wouldn’t come to faith in Christ until five years after he left his last foster home, this last family introduced him to Jesus. For the last several years he was in foster care, the family took him to church just about every week and even involved him in Awana. That’s where he learned John 3:16.

“It was them having me in church that made me realize that the only thing that would last is Jesus,” Hardy said. “I didn’t know what that meant, but I knew I needed to find Jesus.”

Before Hardy was born, his father urged his mother to get an abortion. The state revoked his mother’s parental rights, and she never attempted to get them back.

Today, Hardy serves as the student pastor at Brainerd Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tenn., and is a student at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary. Looking back over his childhood, he says foster care played a foundational role in helping him eventually come to faith in Christ.

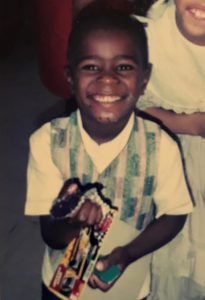

Shaq Hardy spent the first decade of his life shuffling between foster homes. His last foster family introduced him to Jesus. Six years later, as he struggled to find a place to belong, he committed his life to Christ. Today he is serving as a student pastor at Brainerd Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tenn.— Photo courtesy of Shaq Hardy

Hardy’s most traumatic experience in foster care was his last. His father, who was in the Navy, had been stationed nearby and now had room in his house for Hardy. Hardy still remembers how excited he was when his foster family, the one who had taught him about Jesus, told him that he could now move in with his father. For a young boy who had long searched for a home of his own, it was a dream come true, until it turned into a nightmare as he tried to adjust to leaving the family that had raised him for several years.

“I cried the whole night because the normal I thought I wanted isn’t like what I thought it would be,” Hardy said. “In my mind, I had just moved out. My experience with other foster homes is that I would never see this family again. I remember waking up the next morning and feeling emotionally hard. I remember feeling like I was in a cage that no one could get into.”

Years later a counselor would diagnose Hardy with Reactive Attachment Disorder, which means he struggles to develop healthy attachments to other people in his life. He points back to that first night out of the foster-care system and in the home of his biological father when it began.

Moving back into his father’s home began a relentless search for a place to belong. The normally affable Hardy began acting out at school in an effort to fit in with his classmates. After moving to a heavily gang-populated area of Virginia the summer after he turned 13, the search for belonging led him down a path of drugs, alcohol and promiscuity.

“I remember after that summer thinking, ‘That’s not it.’ It was empty. I remember thinking, ‘I don’t want any of that,’ so I never went back to it,” Hardy said.

As he entered high school, Hardy turned to sports. He remembers after he made a disrespectful comment to his coach during a practice, the coach unloaded on him with a double-digit list of reasons he would never start.

“It hurt,” Shaq said. “Football was my god. Football was what I wanted to chase after.”

Determined to prove his coach wrong, Hardy began lifting weights in the morning and in the afternoon. He gave a hundred percent in each practice. Over time, he got better. In his junior year, he became a starter, beating out several seniors. When the announcement came, his first feeling was excitement, but that quickly changed as he realized the accomplishment still wasn’t enough to fix his loneliness.

Shaq Hardy, who serves as the student pastor at Brainerd Baptist Church in Chattanooga, Tenn., preaches at a student gathering. Having seen firsthand the impact of foster care, he encourages Christians to show love to foster children in tangible ways. — Photo courtesy of Shaq Hardy

“I felt just as empty at 16 as I had at 13,” Hardy said. “I got to a point when I felt like I was done with life. I didn’t want to live. I wouldn’t say that I had crazy suicidal thoughts or anything, but I was depressed.”

Recalling his foster family’s relationship with God, Hardy realized he needed Jesus. Eventually, he discovered First Baptist Church of Jacksonville, N.C. (now called Catalyst Church), which embraced him and began to fill some of the void in his life.

“They came around me like family over the course of those 10 months,” Hardy said. “That’s when I found out some really difficult things like my dad wanted to have me aborted. That was one of the hardest days. I had a track meet that day. I found out the day before. I went and ran at the track meet, and I went to the church office with the leaders of the youth group and just bawled. They walked me through it.”

Eventually, at a church camp in Philadelphia, Hardy committed his life to Christ. He’ll be the first to say that decision didn’t solve all his problems. In fact, he says, some of his hardest times emotionally have come since he became a Christian. He still desperately misses the love of a mother he has never known. He is still searching for belonging.

Yet Hardy knows that in Christ, he has a place to belong.

“It really wasn’t until seminary, when I learned more about how to study the Bible, that my perspective on heaven changed,” said Hardy, who has served as a student pastor at Brainerd for the past three years. “I used to think of heaven as a place and when I’m there, I’m home and home forever and nobody will be able to take that away from me. But what’s more amazing than heaven and what an awesome place it will be is that [God] is making His dwelling place with us, the church. It’s not a place. As long as I’m with Him, I’m right where I belong.”

Hardy says that although foster parents must be prepared for the intense demands of parenting children who have been through trauma, he believes it is an incredible opportunity to influence lives.

He said, “If you can pull a kid into your home and show them — not just tell them — that you love them, as they’re acting out and being disobedient and crying with their emotional lives begging for attention in the wrong ways, and you can show them the love of Jesus, even if it doesn’t click, maybe at some point five, six or 10 years later, it will click and they will remember what you showed them about Jesus.” B&R